When it comes to SpaceX, or perhaps more accurately its somewhat eccentric founder and CEO Elon Musk, it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction. For as many incredible successes SpaceX has had, there’s an equal number of projects or ideas which get quietly delayed or shelved entirely once it becomes clear the technical challenges are greater than anticipated. There’s also Elon’s particular brand of humor to contend with; most people assumed his claim that the first Falcon Heavy payload would be his own personal Tesla Roadster was a joke until he Tweeted the first shots of it being installed inside the rocket’s fairing.

So a few years ago when Elon first mentioned Starlink, SpaceX’s plan for providing worldwide high-speed Internet access via a mega-constellation of as many as 12,000 individual satellites, it’s no surprise that many met the claims with a healthy dose of skepticism. The profitability of Starlink was intrinsically linked to SpaceX’s ability to substantially lower the cost of getting to orbit through reusable launch vehicles, a capability the company had yet to successfully demonstrate. It seemed like a classic cart before the horse scenario.

So a few years ago when Elon first mentioned Starlink, SpaceX’s plan for providing worldwide high-speed Internet access via a mega-constellation of as many as 12,000 individual satellites, it’s no surprise that many met the claims with a healthy dose of skepticism. The profitability of Starlink was intrinsically linked to SpaceX’s ability to substantially lower the cost of getting to orbit through reusable launch vehicles, a capability the company had yet to successfully demonstrate. It seemed like a classic cart before the horse scenario.

But today, not only has SpaceX begun regularly reusing the latest version of their Falcon 9 rocket, but Starlink satellites will soon be in orbit around the Earth. They’re early prototypes that aren’t as capable as the final production versions, and with only 60 of them on the first launch it’s still a far cry from thousands of satellites which would be required for the system to reach operational status, but there’s no question they’re real.

During a media call on May 15th, Elon Musk let slip more technical information about the Starlink satellites than we’ve ever had before, giving us the first solid details on the satellites themselves, what the company’s goals are, and even a rough idea when the network might become operational.

Elon reiterated several times that these satellites will be the first of at least three generations of satellites which will eventually make up the Starlink network. They’re closer to the final satellites than the Tintin A and Tintin B technology demonstrators launched in 2018, but still lacking key features which will be necessary for optimum performance.

The biggest omission with these early satellites is the lack of inter-vehicle laser communication links, which means each satellite will have to relay everything through ground stations. In other words, if a Starlink satellite wants to send data to one of its peers, it will have to send it down to a ground station which then routes the information over the terrestrial Internet to another ground station that’s in range of the recipient. This not only increases latency, but requires a large number of ground stations located all over the globe.

To solve this problem, Elon says later versions of the Starlink satellites will use laser communications to form interconnected links, creating a mesh network in space. Data won’t always have to be sent to the Earth and back, and instead can be routed through the satellite network. Of course, ground stations will still be required to ultimately get data to and from the Internet itself, but far fewer of them will be needed and their geographic location will be less critical. This technology, which allows global communications with little to no ground infrastructure, could also be applied to satellite constellations orbiting the Moon or Mars; something SpaceX is almost certainly thinking about on the long-term.

In addition, Elon reiterated that these first 60 satellites don’t feature the “Design for Demise” optimizations which were implemented after the Federal Communications Commission’s expressed concerns over SpaceX’s inability to guarantee that debris from reentering Starlink satellites could be safely contained over the ocean. In their response to the FCC, SpaceX promised that future versions of the satellites would be designed in such a way that they would entirely burn up during reentry, removing any risk that falling debris endangering human life or property.

These first generation Starlink satellites might be missing some key features, but they aren’t exactly placeholders either. While we’ll have to wait awhile before we see laser communication or fully degradable construction, they definitely have some unique capabilities that will likely get the attention of other aerospace players if they prove successful.

According to Elon, these satellites are the first vehicles to ever use a krypton-powered ion drive in space. This type of propulsion was experimented with by NASA back in the early 1990’s, but never progressed into operational status as it was found to be less efficient than similar thrusters powered by xenon. That said, krypton is cheaper than xenon, and with low-cost satellites that are only expected to make occasional orbit adjustments during their relatively short lifespans, using a lower efficiency propellant actually made more economical sense.

On the subject of orbital adjustments, these satellites will also be testing an autonomous obstacle avoidance system which is sure to be of interest given the ever-increasing concerns over “space junk” in low Earth orbit. The satellites will receive orbital debris data from a NORAD database and use that information to decide on their own whether they should perform evasive maneuvers. Traditionally such decisions are made by ground controllers, but with tens of thousands of satellites in the final Starlink network, SpaceX reasoned this was a task that could benefit from automation.

Learning more about the technical aspects of the satellites themselves is interesting, but probably the biggest question most people have about Starlink was just how SpaceX intends to hoist 12,000 satellites into orbit within the next couple of years. For reference, since the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, humanity has put fewer than 9,000 objects into orbit around the Earth. Viewed in that light, one could argue that a satellite constellation of Starlink’s proposed size would represent a new milestone in mankind’s utilization of space.

Learning more about the technical aspects of the satellites themselves is interesting, but probably the biggest question most people have about Starlink was just how SpaceX intends to hoist 12,000 satellites into orbit within the next couple of years. For reference, since the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, humanity has put fewer than 9,000 objects into orbit around the Earth. Viewed in that light, one could argue that a satellite constellation of Starlink’s proposed size would represent a new milestone in mankind’s utilization of space.

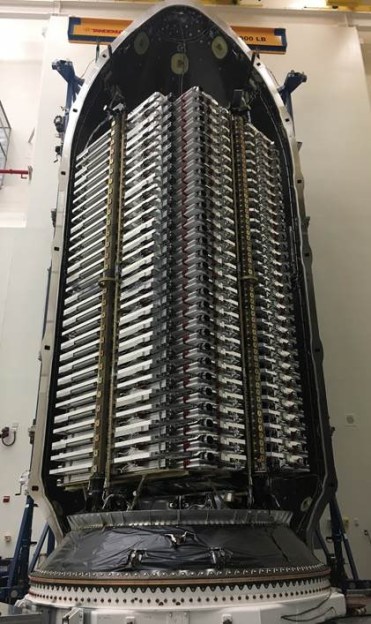

The reusability of the Falcon 9 was a huge piece of the puzzle, but it still wouldn’t be economically feasible unless SpaceX could maximize the number of satellites that could go up in each launch. To that end, they came up with a novel “flat-pack” design for the Starlink satellites. Inside the payload fairing, the satellites are stored in an arrangement not unlike a server rack, and when deployed they unfold their solar arrays and antennas into operational position. Elon admitted there’s a chance a few of them might bounce into each other on the way out, but said that it wasn’t expected to cause any serious issues given how low their relative speeds will be.

With 60 satellites weighing 227 kilograms each, plus the weight of ancillary hardware like the rack itself, this first Starlink launch will tips the scales at 18.5 tons; the most mass a Falcon has ever put into orbit. Even still, Elon said it will cost SpaceX more to launch the Starlink satellites than it did to build them in the first place.

Unfortunately, we didn’t learn a whole lot about when and how consumers can actually sign up for Starlink Internet service. In the best case scenario, Elon estimated it would take another six launches before the network could even be activated, and twelve to provide enough coverage for it to be usable. After that, SpaceX will begin looking for commercial partners to actually start selling Internet service and distributing their phased-array terminals, likely with rural customers to begin with. At least for now it seems like SpaceX would rather partner with traditional ISPs than go to war with them, which will probably come as a disappointment to those who hoped Elon would shake up the telecommunications industry.

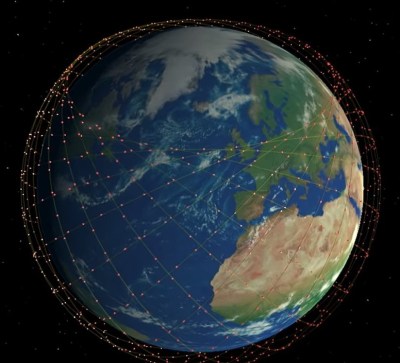

Satellite coverage renderings taken from Mark Handley’s excellent video about Starlink.

Everything We Know About SpaceX’s Starlink Network

Source: HackADay